After leaving my day job, I decided to treat myself to a holiday.

‘I’ve a feeling you won’t be going to The Maldives,’ said someone I told.

No, I explained, I was going on a Library Holiday.

‘Aha,’ they said, ‘solid historian answer.’

You probably want to know what a Library Holiday actually is, but first I’m afraid you’ll have to read my reminder that this coming Sunday, 26th January, at 7pm London Time, My Life In The Past will be holding its first live video chat! Do join me and Top Historian Nathan Amin to discuss the Mystery of the Princes in the Tower.

How can you tune in? The easiest way is to click the button below to download the Substack app. If you enable notifications, the app will give you a nudge when we start. Just tap that, and you’re in. It’s that easy! But do mark your diary now so you don’t forget.

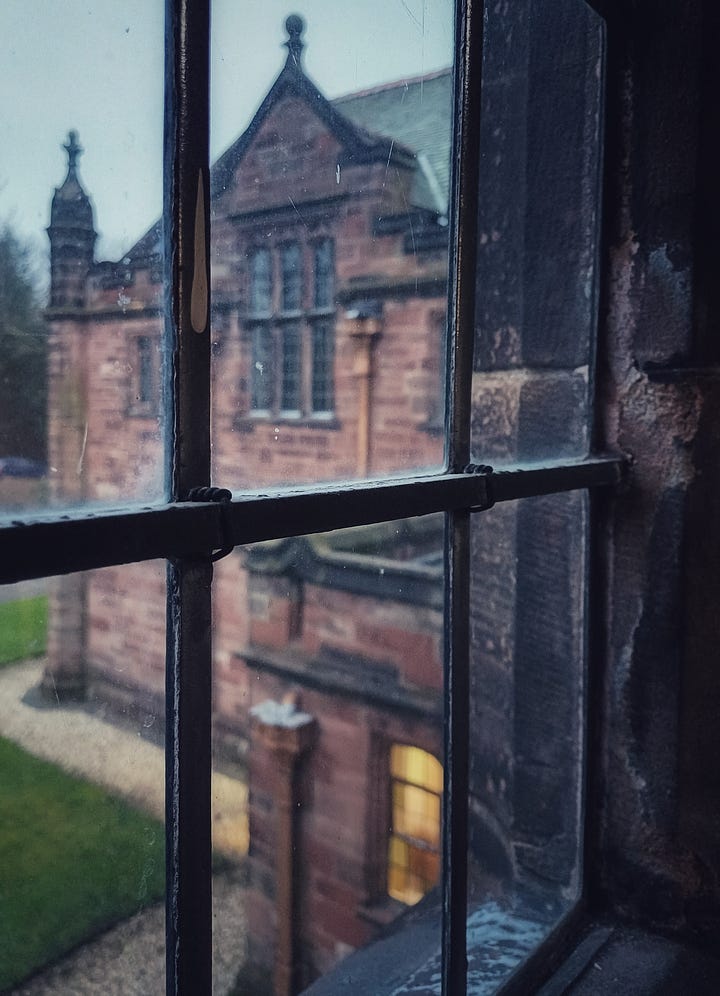

Back to the books. I felt like I was the only one of my friends who hadn’t already stayed at the Gladstone Library, which last week became my home for a few wonderful days. You can sleep there! And get all your meals! And just look at the beautiful reading room:

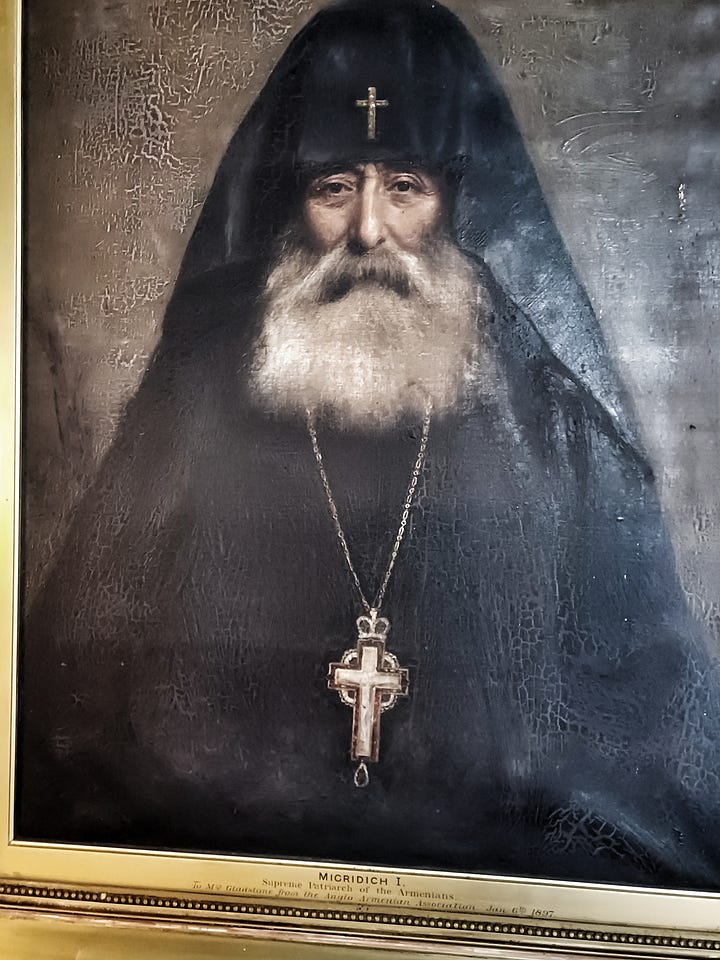

St Deiniol’s Library, as it was originally called, is in North Wales. At the core of its collection are the books owned by four-times Liberal prime minister William Ewart Gladstone, who brought them over from his house in a wheelbarrow.

The present building, erected in 1906 by his children, has an attached hostel ‘for the use of students engaging in the pursuit of divine learning’.

It’s a gothic delight. From my room I could see the churchyard, and at night I heard the tolling of the hours and the hooting of owls. In the quiet corridors I kept expecting to see a black habit swishing away from me round a corner.

I canvassed my friends who’d been before for tips about what to expect.

‘The drive to get there is awful, take your time,’ said one of them. I ignored her because I’d already decided to get the bus from Chester.

The driver took one look at me as I got on and said ‘Ah. You’ll be wanting The Library.’ I don’t know how he knew.

‘After dinner,’ said another, ‘drink red wine by the fire.’ I ignored her. Last Friday night at nine (when you were all hopefully watching Lucy Worsley Investigates The Norman Conquest) I was in the reading room with a book - it stays open until ten.

To one side of me a novelist was tapping away, to the other, someone was reading about Catholic theology. Our combined concentration created a very intense and blissful kind of silence.

‘Take your own sheets,’ said a third. She’d previously had issues with the library’s polycotton. I ignored her, and personally found the bedding perfectly acceptable.

But all three of them emphasised that I should take my boots to walk in the woods of Hawarden Castle, the family home of Mr Gladstone’s wife Catherine – and this time I listened. My boots and I walked to our great content.

I used not to be very fond of Mr Gladstone. I think I took against him because of Queen Victoria’s complaint that he addressed her as if she were a public meeting.

Over time, though, I’ve warmed to him, particularly after reading Roy Jenkins’ giant fruitcake of a biography. I like the way that Jenkins, a politician himself, helped me appreciate Gladstone’s extraordinary political talent.

The queen described him as a ‘half-mad firebrand,’ but I came to admire his commitment to his eccentric hobbies: revering the Almighty, accosting sex workers to offer them his support, and chopping down trees.

Once he was out in the Hawarden woods when a telegram arrived. Queen Victoria wanted him to form a new government. He read it, but didn’t stop chopping for long.

He said just two words: ‘Very Significant’.

Then he got back to work again, and:

‘continued to attack the tree. After a few more blows he rested on his axe and said, ‘My mission is to pacify Ireland.’*

I like the Jenkins biography’s aroma of late-night sittings in the House of Commons, fiery speeches, and delicate machinations that would slowly bring the tectonic plates of public opinion and progressive thought into line.

For me, though, the essence of the strange appeal of living at Mr Gladstone’s Library was nostalgia. Personally, I was very happy when I was a student, going to the library every day, and not looking much further ahead than my next history essay.

My history tutor had an extremely straightforward argument for why anyone should do a history degree.

‘Most of your working life,’ he’d say, ‘will probably consist of writing essays. You might as well learn how to do it.’

I was a bit doubtful. I thought my working life might include wearing a jacket with shoulder pads, and maybe sending faxes.

But in the final sentence of this essay, I shall argue that my history tutor turned out to be right.

*Lord Shaftesbury quoted in Roy Jenkins, Gladstone.

Lucy, I have spent my working life writing essays, and now spend time with my grandchildren helping them to structure theirs! However, I often wonder if I could choose again - I think I should have been a librarian. Being surrounded by books - perfect. Also one of my granddaughters is reading your book about Queen Victoria. The others are on my sofa on their phones. So Lucy - one out of six grandchildren isn’t bad - progress is made at grandma’s house thanks to you Lucy!

Hey Lucy!

What a delightful read about a delightfully sounding library. And who doesn’t love a library. Especially one one can sleep beside.

Count me in for this Sunday. So looking forward to this. You will have at least one fan tuning in from Sydney, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Also a place touched by Indigenous, French, and British history.