Two Sarahs catch a killer

Cracking the very cold case of the Thames Torso Murderer in 1880s London

One particular scene in VICTORIAN MURDER CLUB, a TV series about the Thames Torso Murderer who killed four women in London between 1887 and 1889, has inspired quite a few keyboard warriors to get in touch.

It’s the bit where I ask a pathologist if the Victorian police surgeons did a good job on the original autopsies of the victims, and she says ‘yes’.

‘Gotcha!’ the emails say. ‘You were obviously hoping the police had messed up but they hadn’t. More fool you.’

What my clever gentlemen correspondents don’t realise is that the documentary was framed as an investigation because … it was one.

I didn’t know what we were going to find. We had to explore all the dead ends.

But still, these emails got me thinking … did the Victorian police do a good job?

Well, they certainly tried hard! But they didn’t identify the murderer.

I think that now, today, we have a pretty good idea who he was.

But the mystery was solved using a couple of techniques that just weren’t available to the Victorian police.

First, though, let me fill you in on the background.

In October, 1889, a woman called Sarah Warburton accepted a lift home at night in a rowing skiff on the Thames. The boat was operated by a waterman, the Victorian equivalent of a taxi driver.

39 years old, Sarah was separated from her husband. A mother of three, she was illiterate, and earned a meagre living sewing fur trimmings onto clothes.

She’d been in a pub south of the river, but her home was on the north bank. The new Tower Bridge was still only half finished, hence the need for the boat ride. As she got into this friendly waterman’s skiff, another woman reassured Sarah that ‘she would be perfectly safe with him.’

She was wrong. He went on to rape her on the river.

But on top of that, I believe Sarah Warburton’s attacker was also the Victorian serial killer known as the Thames Torso Murderer.

He’s called this because he dismembered his victims, leaving body parts in and around the river. By the time Sarah Warburton got into his boat in October 1889, four headless torsos had been found: at Rainham, Essex (1887), Whitehall (1888), Battersea (June 1889) and Whitechapel (September 1889).

The murders remained unsolved for 130 years.

But it’s now time to showcase the work of another Sarah: a modern researcher called Sarah Bax Horton, who has – to my satisfaction at least – discovered the culprit.

A former Foreign Office analyst who’s made an inspiring mid-life jump into a new career as a historian, Sarah Bax Horton’s published her work in her book Arm of Eve.

The evidence wouldn’t stand up in a court of law, but it’s still compelling.

Sarah Bax Horton’s breakthrough was to use something the Victorian police could not: a digital newspaper database. She searched it using three filters: the timeframe of the murders, the river itself, and for violent crimes against women.

Building up what today’s criminologists - with knowledge the Victorian police didn’t have - would call a profile of the killer, Sarah Bax Horton had deduced that the Torso Murderer probably committed a string of lesser crimes as well.

Out of Sarah’s search popped the rape of Sarah Warburton, and the name of the waterman who assaulted her: James Crick.

James Crick’s movements perfectly fit the timeline of the crimes, and he had something crucial for these river-based attacks: the privacy and mobility of his boat. And there’s more: the newspapers further reveal that after earlier accusations of domestic violence and rape, the police had failed to convict Crick.

If they had done this, his later victims might have lived.

During his attack on Sarah Warburton, Crick told her he would ‘settle’ her, ‘as I have done other women that have been found in the Thames.’

But this time, a passing police officer heard Sarah’s screams and arrested him.

It was Sarah Warburton’s courtroom testimony, bravely given, that put him away in prison.

And after that, the Thames Torso Murders stopped.

Now the series is finished, I’m raising a glass to the two women who succeeded where the Victorian police failed.

I love the fact they’re both named Sarah.

Firstly, the nineteenth-century Sarah Warburton, whose testimony put the Thames Torso Murderer behind bars.

And the twenty-first century Sarah Bax Horton, whose patient detective work allows us to know and celebrate that fact.

For your diary: on Sunday 8 February, 7pm London time, subscribers will be enjoying our first live video chat of 2026!

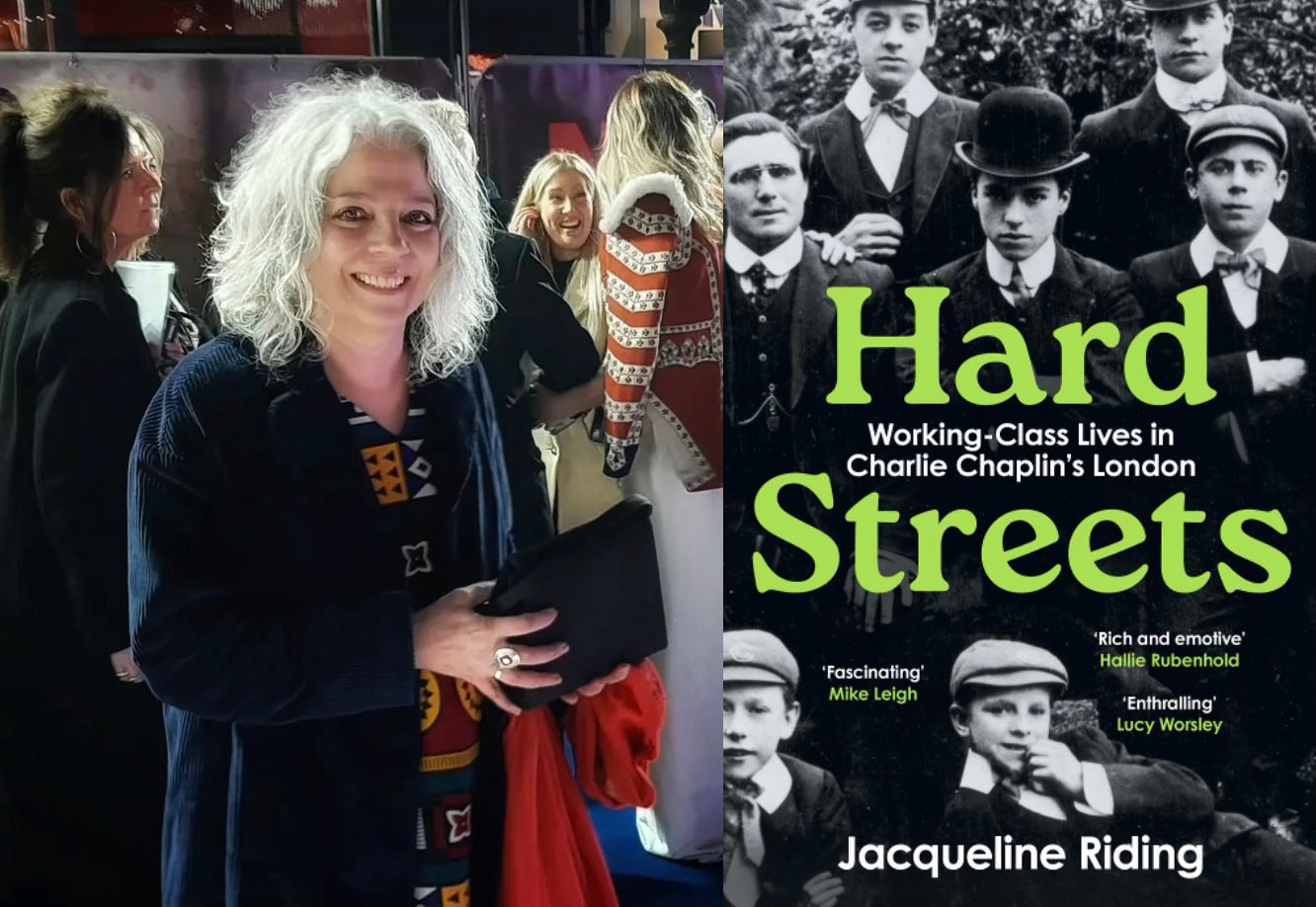

I’ll be talking to historian and good friend Jacqueline Riding about her new book Hard Streets. It’s about Charlie Chaplin’s family and early life, and the history of working class lives in general in the part of South London where we both live. Join us!

What a fascinating history and I am so thankful for the courage of Sarah Warburton to testify to what she experienced on that “safe” boat journey. It does make me wonder though about the woman who told Sarah she would be perfectly safe riding with this man. Had she safely ridden with him in his boat or was she the “front person” luring women to him? A new mystery, perhaps?

Thanks Lucy, as I said earlier, I really enjoyed your 'Team Investigation' style. Even more enjoyed the fact that 2 authors - convinced they'd identified the killer: one linking to Jack The Rpr & the other 2 the Poisoner - were well blown out of the water by Forensic & Crime Psychology work.

Will definitely follow up Sarah's book and look forward to the Chaplin one: seen it favourably reviewed elsewhere. PS loved your BBC History article too.